Another video and commentary coming in the next day . . .

Sunday, February 26, 2006

Saturday, February 25, 2006

We miss La Houston

Pavarotti's joined by Sting, Elton John, and an operatic Whitney Houston for the weirdest "La donna e mobile" you'll ever hear. 1994 was a really long time ago.

Karita Mattila and Lorraine Hunt Lieberson stop by for Gurrelieder with James Levine

The Boston Symphony programmed three performances of Schoenberg's Gurrelieder conducted by music director James Levine and featuring a stellar cast of soloists and the never-disappointing Tanglewood Festival Chorus.

This was my first encounter with the work. I despise listening to recordings, and if I have a chance to experience a concert more than once, I allow my first time with the program (if I am unfamiliar with the work(s)) to be at the live performance. I attended my first on Thursday, February 23rd, and I will return tonight.

I didn't do my homework prior to Thursday's performance, nor did I attend the preconcert lecture. Even worse, I didn't even read the program notes. But all will be corrected tonight. Sometimes it's good to experience something without all of the context. Anyway, I'm going to focus on a few things here, things I picked up.

First, Karita Mattila is a stunningly beautiful woman. I refrain from using the term "opera hot"; she's just hot. She has a profound sexiness that suggests both intimacy and distance. That combination of warmth and reserve makes her irresistible. Decked in soft lilac and pearls, her fingertips capped by long red nails, her left forearm covered in pave diamonds, she was the picture of glamour. A kind of kitschy glamour, but a very Karita glamour, right down to the gold pumps and the four rings, including a thumb ring.

Johan Botha, meanwhile, sported a bold mullet. Yes, a mullet. I'll move on now.

Mattila and Botha were often barely audible during Part I. Mattila, especially, seemed to be marking. But why would she do that? More likely is that Levine wasn't careful (as he wasn't during the Tchaikovsky with Renee Fleming at Carnegie Hall) and allowed the singers to be covered. After all, this was a ridonkulously (my new favorite word) large orchestra--have you ever seen four harps!?--requiring an extension of the stage and the use of every square inch. The problems were definitely corrected in the second half.

Mattila (I'm not so interested in Botha, who is a fine singer but, I mean, he's got a mullet) sang gorgeously throughout, and her last bit, sung forte and then ultra-sweetly, was to die for. This was the text (in translation):

And when you awaken,

With you, there upon the couch,

clad in new beauty, you will see

a young a radiant bride.

So let us drain our goblets in a toast to him,

mighty, adorning Death:

for we go to the grave,

like a smile, dying,

in a rapturous kiss.

OK. Sounds good.

What can I say about Lorraine Hunt Lieberson? Critics have famously run out of glowing encomiums for her. I'll shamelessly try one. It's not just her voice. It's her presence. There's a certain calm, a quiet, that reminds me of the desert, where she makes her home. Majestic and, paradoxically, silent, she's what Earth would sound like if it had a voice. In the presence of Lieberson, one feels a sense of wonder. I think it's because every time we hear her, something from the profound depths, something beyond music and objects and time, tries to speak to us. Her voice is a vessel.

There's an orchestral interlude after Waldermar's (Botha's) final passage in Part I, which closes with the Wood-Dove's extended monologue (Lieberson). During the interlude, Lieberson quietly emerged, like a spirit, from stage left. Clothed in shades of taupe and brown, her short brown and dark blonde hair coiffed close to her head, her neck caressed by a strand of champagne pearls, she radiated peaceful beauty.

Her voice? It's a complex sound. It's not a gem-like sound. It's a sound of the earth, of mountains. The ocean. If Podles is a 1 on the nuance scale, Lieberson is a 10. She was born to be a storyteller, a quality that is, frankly, what great singing is all about. In her voice the Wood-Dove's refrain--"I flew far, sought for grief, and have found much!"--broke my heart.

The last thing I'll say about Gurrelieder is that it has a ridonkulously exciting finale, and here I give major props to the Tanglewood Festival Chorus, which truly shone. All soloists returned for the madly ecstatic ovations--the entire audience immediately rose just as the last chord faded--at the concert's conclusion. Many kisses were exchanged on stage. (Note: Lieberson is a one-cheek kisser, while Mattila plants a firm one on each.) Hm, musta been nice up there.

This was my first encounter with the work. I despise listening to recordings, and if I have a chance to experience a concert more than once, I allow my first time with the program (if I am unfamiliar with the work(s)) to be at the live performance. I attended my first on Thursday, February 23rd, and I will return tonight.

I didn't do my homework prior to Thursday's performance, nor did I attend the preconcert lecture. Even worse, I didn't even read the program notes. But all will be corrected tonight. Sometimes it's good to experience something without all of the context. Anyway, I'm going to focus on a few things here, things I picked up.

First, Karita Mattila is a stunningly beautiful woman. I refrain from using the term "opera hot"; she's just hot. She has a profound sexiness that suggests both intimacy and distance. That combination of warmth and reserve makes her irresistible. Decked in soft lilac and pearls, her fingertips capped by long red nails, her left forearm covered in pave diamonds, she was the picture of glamour. A kind of kitschy glamour, but a very Karita glamour, right down to the gold pumps and the four rings, including a thumb ring.

Johan Botha, meanwhile, sported a bold mullet. Yes, a mullet. I'll move on now.

Mattila and Botha were often barely audible during Part I. Mattila, especially, seemed to be marking. But why would she do that? More likely is that Levine wasn't careful (as he wasn't during the Tchaikovsky with Renee Fleming at Carnegie Hall) and allowed the singers to be covered. After all, this was a ridonkulously (my new favorite word) large orchestra--have you ever seen four harps!?--requiring an extension of the stage and the use of every square inch. The problems were definitely corrected in the second half.

Mattila (I'm not so interested in Botha, who is a fine singer but, I mean, he's got a mullet) sang gorgeously throughout, and her last bit, sung forte and then ultra-sweetly, was to die for. This was the text (in translation):

And when you awaken,

With you, there upon the couch,

clad in new beauty, you will see

a young a radiant bride.

So let us drain our goblets in a toast to him,

mighty, adorning Death:

for we go to the grave,

like a smile, dying,

in a rapturous kiss.

OK. Sounds good.

What can I say about Lorraine Hunt Lieberson? Critics have famously run out of glowing encomiums for her. I'll shamelessly try one. It's not just her voice. It's her presence. There's a certain calm, a quiet, that reminds me of the desert, where she makes her home. Majestic and, paradoxically, silent, she's what Earth would sound like if it had a voice. In the presence of Lieberson, one feels a sense of wonder. I think it's because every time we hear her, something from the profound depths, something beyond music and objects and time, tries to speak to us. Her voice is a vessel.

There's an orchestral interlude after Waldermar's (Botha's) final passage in Part I, which closes with the Wood-Dove's extended monologue (Lieberson). During the interlude, Lieberson quietly emerged, like a spirit, from stage left. Clothed in shades of taupe and brown, her short brown and dark blonde hair coiffed close to her head, her neck caressed by a strand of champagne pearls, she radiated peaceful beauty.

Her voice? It's a complex sound. It's not a gem-like sound. It's a sound of the earth, of mountains. The ocean. If Podles is a 1 on the nuance scale, Lieberson is a 10. She was born to be a storyteller, a quality that is, frankly, what great singing is all about. In her voice the Wood-Dove's refrain--"I flew far, sought for grief, and have found much!"--broke my heart.

The last thing I'll say about Gurrelieder is that it has a ridonkulously exciting finale, and here I give major props to the Tanglewood Festival Chorus, which truly shone. All soloists returned for the madly ecstatic ovations--the entire audience immediately rose just as the last chord faded--at the concert's conclusion. Many kisses were exchanged on stage. (Note: Lieberson is a one-cheek kisser, while Mattila plants a firm one on each.) Hm, musta been nice up there.

Friday, February 17, 2006

Ewa Podles

A couple years ago, Jeff Corwin, the sexy TV naturalist, was in a bush somewhere showing us elephants. They were moving quietly in a forest, and since the animals sometimes charge unexpectedly and rapidly, it was a scary, scary situation. Corwin remarked, "What you do in the privacy of your underpants is your own business!"

I had the same thought during contralto Ewa Podles's recital in Boston tonight. As someone once said of another singer's performance: when it was all said and done, there was not a dry seat in the house.

Report coming later.

Update:

I have been slacking off way too much. Thanks to all the friendly people who visit this blog on a regularly basis. You have more faith in me than I do. Sorry to disappoint you with my profound laziness.

OK, enough guilt.

Jordan Hall is a rather intimate venue, and Celebrity Series uses it for the vocal recitals that it expects won't draw much of a crowd. (The significantly larger Symphony Hall is used for the likes of Renee Fleming, Deborah Voigt, and Cecilia Bartoli.)

Still, it's often a small but enthusiastic crowd, and this Friday night was no exception. Podles is known to have a cultish following, though she's not terribly familiar to Bostonians, given that this was the occasion of her Boston debut.

When Podles made her entrance, my eyes quickly shifted to her gorgeous accompanist, Ania Marchwinska, an elegant blonde sporting a sparkling snakeskin-textured black gown whose fit suggested couture. Podles, on the other hand, wore an unflattering sausage-like concoction that only emphasized her stumpiness. (Sorry.)

So, I got myself prepared and opened the program to the texts of the first group, Chopin songs. I thought I would read along, but when Podles opened her mouth, my jaw dropped and the program fell on my lap, neglected, for the rest of the group.

How to describe the voice? Her recordings, with which I'm not terribly familiar, do not do justice to the size, resonance, and impact of her instrument. The middle voice is pleasant, large, and bright. It's a low, bright sound. The lower register is full of baritonal resonance and can be quite thrilling. The top, at least this night, was quite short and strained, but it has been known to be agile and intense.

Rossini's Giovanno d'Arco is a great showpiece and it's perfect for a recital. In the piano introduction, I noticed Marchwinska's weird piano playing. What was she on? And no page turner? She actually paused to turn the page. And she has a Masters in Accompanying from Julliard? OK . . .

So, the first stunning moment in the Rossini came at the extended melisma on "mormorar" in the first verse, a phrase that also included one of the extremely low notes of the piece. This ridonkulously virtuosic cantata, with its fiery coloratura, numerous octave leaps, and, quite frankly, showing-off opportunities, was a winner.

Podles exhibited a certain softness and fluency (in more senses than one) in the Chopin, but in the Rachmaninov, she showed some rough edges. She lacks the legato loveliness of a Renee Fleming in "In the Silence of the Night." Requiring restraint and elegance, it's a difficult song, and she didn't pull it off. Her instrument is large and sometimes unwieldy. But in this group there was still much of her gorgeous tone, acres of pave rubies and diamonds. Holding on to the last pitch of "She is as Beautiful as Noon" created one of the great moments of the recital--as it grew it size and sound, it as was though she'd torn open a space in the hall, revealing a sparkling night sky. Does that make sense? Good.

I thought it was a bad idea to close with the Brahms Zigeunlieder, which doesn't end very climactically. Most notable was probably "Kommt dir manchmal," which was as lyrical as she got all evening.

As for the encores (there were two), "Cruda sorte" from L'Italiana was terribly fun, and we got a glimpse of Podles's comic sensibility. She's pretty old school; she doesn't go for cinematic subtlety, but uses large physical and vocal gestures. Case in point: to indicate that she'd be singing no more encores, she crossed her neck rather aggressively, albeit with a smile.

I had the same thought during contralto Ewa Podles's recital in Boston tonight. As someone once said of another singer's performance: when it was all said and done, there was not a dry seat in the house.

Report coming later.

Update:

I have been slacking off way too much. Thanks to all the friendly people who visit this blog on a regularly basis. You have more faith in me than I do. Sorry to disappoint you with my profound laziness.

OK, enough guilt.

Jordan Hall is a rather intimate venue, and Celebrity Series uses it for the vocal recitals that it expects won't draw much of a crowd. (The significantly larger Symphony Hall is used for the likes of Renee Fleming, Deborah Voigt, and Cecilia Bartoli.)

Still, it's often a small but enthusiastic crowd, and this Friday night was no exception. Podles is known to have a cultish following, though she's not terribly familiar to Bostonians, given that this was the occasion of her Boston debut.

When Podles made her entrance, my eyes quickly shifted to her gorgeous accompanist, Ania Marchwinska, an elegant blonde sporting a sparkling snakeskin-textured black gown whose fit suggested couture. Podles, on the other hand, wore an unflattering sausage-like concoction that only emphasized her stumpiness. (Sorry.)

So, I got myself prepared and opened the program to the texts of the first group, Chopin songs. I thought I would read along, but when Podles opened her mouth, my jaw dropped and the program fell on my lap, neglected, for the rest of the group.

How to describe the voice? Her recordings, with which I'm not terribly familiar, do not do justice to the size, resonance, and impact of her instrument. The middle voice is pleasant, large, and bright. It's a low, bright sound. The lower register is full of baritonal resonance and can be quite thrilling. The top, at least this night, was quite short and strained, but it has been known to be agile and intense.

Rossini's Giovanno d'Arco is a great showpiece and it's perfect for a recital. In the piano introduction, I noticed Marchwinska's weird piano playing. What was she on? And no page turner? She actually paused to turn the page. And she has a Masters in Accompanying from Julliard? OK . . .

So, the first stunning moment in the Rossini came at the extended melisma on "mormorar" in the first verse, a phrase that also included one of the extremely low notes of the piece. This ridonkulously virtuosic cantata, with its fiery coloratura, numerous octave leaps, and, quite frankly, showing-off opportunities, was a winner.

Podles exhibited a certain softness and fluency (in more senses than one) in the Chopin, but in the Rachmaninov, she showed some rough edges. She lacks the legato loveliness of a Renee Fleming in "In the Silence of the Night." Requiring restraint and elegance, it's a difficult song, and she didn't pull it off. Her instrument is large and sometimes unwieldy. But in this group there was still much of her gorgeous tone, acres of pave rubies and diamonds. Holding on to the last pitch of "She is as Beautiful as Noon" created one of the great moments of the recital--as it grew it size and sound, it as was though she'd torn open a space in the hall, revealing a sparkling night sky. Does that make sense? Good.

I thought it was a bad idea to close with the Brahms Zigeunlieder, which doesn't end very climactically. Most notable was probably "Kommt dir manchmal," which was as lyrical as she got all evening.

As for the encores (there were two), "Cruda sorte" from L'Italiana was terribly fun, and we got a glimpse of Podles's comic sensibility. She's pretty old school; she doesn't go for cinematic subtlety, but uses large physical and vocal gestures. Case in point: to indicate that she'd be singing no more encores, she crossed her neck rather aggressively, albeit with a smile.

Sunday, February 05, 2006

A story of destructive rural homophobia

Thank you, David Mendelsohn, for this. Mendelsohn provides a much-needed polemic that gently yet cogently exposes the "love story" and "universal" marketing-speak of the studio, the filmmakers, and the cast of Brokeback Mountain. He observes: "Both narratively and visually, Brokeback Mountain is a tragedy about the specifically gay phenomenon of the 'closet'—about the disastrous emotional and moral consequences of erotic self-repression and of the social intolerance that first causes and then exacerbates it." His convincing reading is long overdue. To Mendelsohn's insightful analysis (I don't think he gets everything right, but he gets the big picture, so to speak), I'll add something that Annie Proulx writes in her essential "Getting Movied". This passage sheds light on another aspect of specificity (the first being homosexuality), that of the western setting:

The two characters had to have grown up on isolated hardscrabble ranches and were clearly homophobic themselves, especially the Ennis characters. Both wanted to be cowboys, be part of the Great Western Myth, but it didn't work out that way; Ennis never got to be more than a rough-cut ranch hand and Jack Twist chose rodeo as an expression of cowboy. Neither of them was ever a top hand, and they met herding sheep, animals most real cowpokes despise. Although they were not really cowboys (the word "cowboy" is often used derisively in the west by those who do ranch work), the urban critics dubbed it a tale of two gay cowboys. No. It is a story of destructive rural homophobia. Although there are many places in Wyoming where gay men did and do live together in harmony with the community, it should not be forgotten that a year after this story was published Matthew Shepard was tied to a buck fence outside the most enlightened town in the state, Laramie, home of the University of Wyoming. Note, too, the fact that Wyoming has the highest suicide rate in the country, and that the preponderance of those people who kill themselves are elderly single men.

A story of destructive rural homophobia. "Rural" refers to the specifically western setting, "homophobia" to the hatred of homosexuality, and these are the two essential elements of the story. Proulx expresses this theme in several ways, and the central way is through the character of Ennis, who bookends her story (and, in a different way, the movie). It's a tragedy when homophobia operates from the outside (Jack Twist's fate), but it's also tragic when the battle rages in one person's soul. Ennis's internalized homophobia makes it impossible for him to love. You can't love if you hate how you love.

Update: You can find Proulx's essay online here.

The two characters had to have grown up on isolated hardscrabble ranches and were clearly homophobic themselves, especially the Ennis characters. Both wanted to be cowboys, be part of the Great Western Myth, but it didn't work out that way; Ennis never got to be more than a rough-cut ranch hand and Jack Twist chose rodeo as an expression of cowboy. Neither of them was ever a top hand, and they met herding sheep, animals most real cowpokes despise. Although they were not really cowboys (the word "cowboy" is often used derisively in the west by those who do ranch work), the urban critics dubbed it a tale of two gay cowboys. No. It is a story of destructive rural homophobia. Although there are many places in Wyoming where gay men did and do live together in harmony with the community, it should not be forgotten that a year after this story was published Matthew Shepard was tied to a buck fence outside the most enlightened town in the state, Laramie, home of the University of Wyoming. Note, too, the fact that Wyoming has the highest suicide rate in the country, and that the preponderance of those people who kill themselves are elderly single men.

A story of destructive rural homophobia. "Rural" refers to the specifically western setting, "homophobia" to the hatred of homosexuality, and these are the two essential elements of the story. Proulx expresses this theme in several ways, and the central way is through the character of Ennis, who bookends her story (and, in a different way, the movie). It's a tragedy when homophobia operates from the outside (Jack Twist's fate), but it's also tragic when the battle rages in one person's soul. Ennis's internalized homophobia makes it impossible for him to love. You can't love if you hate how you love.

Update: You can find Proulx's essay online here.

Friday, February 03, 2006

Ich bin bereit, Tetrarch

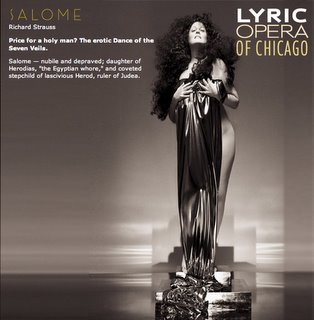

Deborah Voigt as Salome in an announcement for Lyric Opera of Chicago's 2006-07 season. As ever, click image for larger.

Debbie, you lost all that weight and you look gorgeous. I was there on your birthday in 2001--three years before the operation--when you sang your first Salome on a rainy night in the Berkshires. You made your entrance, and the audience, too immature to handle your size, giggled. (They also laughed at Salome's determination for the head, marked by the repeated command, "Give me the head of Jokanaan." Ah, the disadvantages of projected titles.)

From the looks of it, you're quite ready to take it to the stage. Whether the world is ready for what you've got to show, we'll see come November. But my guess is they won't be laughing.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)